Scroll down for Chinese translation

by Eric Kit-wai Ma

2020 was a difficult year for people all around world. It was especially difficult for the people in Hong Kong who were not only burdened by the pandemic, but by acute political crises as well. Many are considering leaving the city. Pessimistic sentiments are widespread. Occasionally, people cheer each other up with words of hope - “We shall overcome,” some say. But more find it difficult to swallow the continued decay of the city.

Last summer, I wrote an essay on the power of hope based on some of the writings of philosopher Gabriel Marcel. He said that amidst the darkness of deep despair, there is a yearning for light and redemption. Like many of my fellow Hongkongers, I have witnessed the rapid deterioration of the rule of law, free speech, and many other things we cherished in our everyday life. Hoping against hope, much like whispering in the dark, has been depleted of applicable meanings. But a few months ago, I took a course on TAE from Nada Lou and have been rethinking the meaning of hope ever since.

Over the past two years, I have participated in various classes and Zoom meetings organized by Edward Chan, one of the founders of the Hong Kong Focusing Institute. I came to know Edward’s teacher, Nada, when I asked about Gendlin’s take on issues concerning faith, religion and spirituality. I got a reply from Nada with a video clip of Gendlin talking about his “cat theology” which inspired me to write for my weekly column another piece on the contrast between religiosity and spirituality. Then, someone from the group came up with the idea of inviting Nada to lead a Zoom course for us. Not thinking it would come to fruition, I was surprised when a small group of eight of us were gathered around the computer screen with Nada in just two-months’ time.

At first, I thought this Thinking at the Edge (TAE) course was another version of Focusing. I soon learned that TAE is a combination of felt sensing and analytic thinking. I had watched a few video clips on TAE previously, but hadn’t registered its relevancy. I do know a bit about Gendlin’s philosophy of knowing, by felt sensing, the emerging ideas from the implicit. According to him, this is where new and unique philosophic knowledge can be originated. That said, I had no idea how TAE could be applied to my life. Amusingly, I was caught by a strong sense of synchronicity in the first Zoom session.

For a few months before meeting Nada, I had been experimenting with a new mode of writing. Whereas before, I would plan ahead when writing my column, sometimes point by point with a preconceived structure, now I was beginning to wait for something to unfold before me. This involved some elements of Focusing, waiting for something written upon my senses, and writing from that something I felt. The writing process was not clear to me yet. The only word to describe it is WAIT. Right at the very beginning of the course, when Nada explained the basics of TAE, it dawned on me to see that "Thinking At the Edge" was exactly what I needed at that particular juncture. Throughout the six sessions of this elementary TAE course, I Focused on the words “anticipatory waiting,” exploring the rich meanings behind my weekly writing ritual by checking back and forth with concepts and felt senses.

Towards the end of the course, the group of us summarized the projects we had developed. When each of the small projects were placed side by side, we felt a faint ray of hope shine through the dire situation in Hong Kong. This was an unexpected turn. Personally, it was a hint for me to rethink what hope is for Hongkongers who are facing the challenge of a liberal city having fallen into tight political control. Maybe we could regain a sense of hope by thinking at the edge and working out what we discovered. In a way, hope is not just an abstract concept - a conviction, a longing for a better tomorrow - it is more. Hope could be fleshing out when we answer the call of our time in a manner unique to each of us, embodied in our life, and embedded in the society at large.

In Nada’s classes, we paid attention to the small details in our daily routines. Most of us had been practicing Focusing for a long while. As for me, a beginner, I was interested in relating Focusing with my previous experiences in research and teaching. Before my retirement, I taught qualitative research methodology for many years and did quite a lot of ethnographic studies. I noticed that Focusers and ethnographers are both trained to attune to the minute sensations, stimulus and feelings of the situation, with Focusing being more into the unknown dimensions of the body. Sometimes I borrowed Heidegger’s concept of Being-in-the-world (Dasein) when I discussed with my research students the theoretical assumptions of ethnography. In any given situation, the ethnographer is not an isolated and objective observer, s/he is embedded in the field, interacting with the things and people s/he is researching. The inter-penetrative nature of Being-in-the-world is the foundation of ethnographic understanding. There is a little bit of you in me; there are some bits of the world in me too. Being-in-the-world is extensively vast and it is also privatively minute, inside the implicit realm of the individual body.

Dasein is a philosophical concept. For Focusing, Being-in-the world is an embodied practice. Felt senses are emerging from within the body, and bodies are situated in particular life worlds. We bear the imprints of our time and each individual marks his or her life story onto the world. Undeniably, the social unrest of 2019 and the pandemic in 2020 have changed Hong Kong radically. The city we know is gone. It is estimated that 5-8% of the population will migrate to other countries in 2021. The recent social changes have left profound impacts on those who stay. Fresh experiences and rich meanings are fostering in the community. Each individual is struggling to find a way to sail through turbulent tides and turns. I believe these are the implicit realms where Hongkongers could find hope.

Nada worked with us on the first five steps of TAE. The first step of TAE is to “choose something you know and cannot yet say, that wants to be said.” The eight of us had different ideas to work on: doing voluntary work, engaging in therapy and counselling, trying out a new working style, being more active in building up friendships, etc. Then, we spelled out the public meanings of the keywords in our project. It was a fruitful exercise when we checked these public meanings with our felt senses and recognized “that’s not what I meant.” Then, we tried to describe these meanings in full, using fresh language unique to us individually.

Nada saved step two for the second-to-last session, which I think was a wise move. We worked on the paradoxical nature of our implicitly felt project. “Paradox is a promise,” Nada said. It really is. Things inside us which are at the edge of our awareness - or even at the edge of our existence, beyond our comfort zone, at the crossroad – surely, they are full of paradoxes, running in different directions, unresolved by logical thinking. These implicit meanings and experiences are raw and new, untamed by public meanings of known vocabularies. We toyed with these sentences:

- Voluntary gift has a price.

- Welcoming suspense is fulfilling the promise of living.

- Recovering is not returning to the original state.

- I know it is not wrong, but it is not right.

These paradoxes bring richness and energies.

My TAE journey has inspired me to reconsider the existential nature of hope for Hong Kong in this particular point in time. Hong Kong is a vibrant city. People here are mostly ethnic Chinese, but because of some unique historical circumstances, Hongkongers have developed a modern and cosmopolitan culture different from other Chinese communities. We are Chinese, but not quite. We are westernized, but not quite. As a former colony, Hong Kong is still carrying some of the British legacies. In the post-war years, for more than five decades, this vibrant and pragmatic Hong Kong culture has stabilized and we are used to this in between quality.

The big shock of 2019 and 2020 has been the sudden demise of this relatively stable socio-cultural system of Hong Kong. For me, the previous two years have been difficult, but being in this city, I feel connected. I am standing right at the edge of a big social transformation and my life story is having a few significant turns. I am sure many Hongkongers feel the same way as I do: there are unfolding felt senses on the individual and collective level. In a way, hope is not that remote and abstract; it could be embodied in these freshly formed experiences.

Nada concluded our class by sharing Gendlin’s idea of the divine call. The felt sense of an individual can be seen as part of this call. It is a unique invitation and can’t be fleshed out by any other human being on earth. I remember Gendlin’s cat theology, mentioned at the beginning of this essay. Gendlin’s cat felt his presence when the cat was sitting next to him on the sofa, but the cat didn’t know where he bought the cat food and what he was doing at the seminars and forums far away from home. It was a world beyond the cat’s understanding, but the felt sense of togetherness was there. Gendlin refrained from affiliating himself with specific religious institutions, but he could share the felt sense of his connectedness with the Divine, like his cat was with him. This cat theology strikes a chord in me. There has been a call for me to write in a new mode, to wait for a freshly emerging felt sense and write about it.

The TAE course helped me to think clearly at the edge and offered fresh wordings about that something I couldn’t yet say. After working on the first five steps of TAE, I came up with this, which is much more than the word WAIT:

I write with anticipatory waiting, like a boy leaning forward, looking around, expecting something to happen. Meanwhile, this waiting is also contemplative, looking inward, felt-sensing the implicit from within me, and crossing with the hearts and minds of the people I have met. This waiting is suspenseful and anxious, hanging in mid-air, as there is the possibility of waiting in vain. Have faith in the unfolding stories, whether they bring agony and despair, excitement and fulfilment, it is a process of growth and discovery.

In the last week of 2020, I wrote about my TAE experience in laymen’s terms and encouraged Hongkongers to pause and felt sense their own “something they can’t yet say.” If they can articulate that little something, it is a gift to Hong Kong.

I ended my essay with a New Year wish for 2021:

We turn our heads, interested in something not yet clear. It is a calling, from the Universe, the ONE seeing something in us, this something is unique, when we respond, from within, and from our Being-in-this-world and far beyond, we are connected. Thinking at our own unique edges of the moment, it is raw, new and exceeds all existing vocabularies. If articulated, it is a gift to us and the world, however small, it is a contribution to humanity. Especially in Hong Kong, our beloved home, in this difficult time when all roads have been blocked, felt sensing the freshly unfolding experiences, a silent but persistent call from the GOOD of all, the gift would die with us if unanswered, but if the invitation is accepted with care, a ray of hope will shine through the edge of our life.

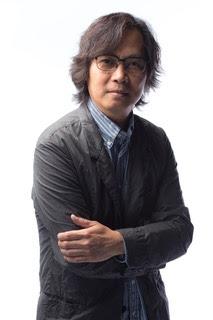

Eric Kit-wai Ma, Ph.D. is a retired professor having taught at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, School of Journalism and Communication where he specialized in Hong Kong cultural identity and popular culture. Retiring early at the age of 56, Eric Ma is now a writer with a column in the popular Chinese newspaper, “Ming Pao.” He is the author of several academic books, including Culture, Politics, and Television in Hong Kong (Routledge, London), Tales from a Bar and a Factory: Urban Study in South China (People’s Press, Nanjing), and his most recent book, Resilience: Clearing a Space in Difficult Times (Breakthrough, HK).

2021年希望的功課

馬傑偉

2020,絕境之年,人與人相隔在疫症的距離,生活翻天覆地;年初病毒壓境,神經拉得繃緊;七月香港國安法治下至今,政治神經拉斷;港人在疫症與政情夾擊下,焦慮不安整整一年,都累了,麻木了。立法會癱了,新聞機構被斷臂,異見人士被控、被捕、被囚。網上流傳一句﹕「你想點就點啦!」疫情對打工仔的生計影響更甚,家累沉重,冇錢開飯,慘過冇得示威遊行。年中在本欄介紹過哲學家 Gabriel Marcel有關希望的分析,希望就是確認苦難不會永續不止,「愈意識到黑暗的深沉,就愈嚮往光明的救贖。」想不到 2020將盡,黑暗遠超想像,如何在困境中懷有希望?如何把抽象的信念化為行動?

由2019至2020,一年多的社會動盪,港人百感交雜。本來是有點兒希望的;猶記得,於街頭衝突最猛烈之時,心焦憤怒,渴望政局有所突破,但一次又一次失望,沒有和解、沒有對話、沒有調查真相的機會。及後疫症全球爆發之後,曾經有幾個月,目睹美國為首的西方國家,對中共政權擺出強硬姿態,令港人隱隱然希望政局會有一絲轉機。但最後香港還是加速內地化。美國政局詭異,歐盟各有危機。港人開始明白到,希望外力拯救香港,根本不着邊際。而最近這兩個月,政局繼續滑進深谷。香港路路不通,又如何保持希望呢?就算口中唸唸有詞,「苦難有盡頭、希望在明天」,你唸一百次吧,但現實生活也有無從發力之感。「希望」兩個字,變得空洞又脫離現實。

這兩年,參加了陳志常老師的課,十多位同學,隔周一聚,分享生命自覺的體驗。志常老師七十多歲;他的老師 Nada Lou身在加拿大,比他大十多歲;而Nada的老師,則是創立生命自覺的 Eugene Gendlin。不知是誰提起,問Nada會否開班授徒?因緣際會,我們八個學生,就在十一月開始,每星期在網上跟 Nada 學習。感覺好像跟師祖上山學法,完全沒有心理準備,本以為都是靜觀自覺之類,怎料她教授的是一種叫 Thinking At the Edge (TAE) 的思考法。

幾年前去世的Gendlin,是芝加哥大學的言語哲學家,用理性思考,也強調身體感應。留傳於世的生命自覺法 (Focusing),透過意感 (felt-sense) 去探索身體的智慧。TAE是他哲學思想的一部分,較為艱深,涉及身體感受,對照嚴謹思考,然後用新鮮的語言,表述新體驗。這種思考法,很難在這篇短文說得清楚。但我可以概述一下,集中談一談在艱難的時代,如何借用 TAE「實踐」希望。亦即是說,我覺得希望不單是願景,而是實際可操作的功課。

港人在困境中生活一年多,新的感受和經驗慢慢形成。不少人實在承受不了,尤其擔心子女教育,若你選擇移民他鄉,祝福你在彼邦找到愜意的生活。留在香港的人,無可避免的,要面對和適應中共的鐵腕管治。過去半年,嚴刑峻法,苛政如虎,蛇鼠盡出,每一次打擊,都難堪難捱。但生活有綿密的肌理,不要低估人的生存本能。消極來說是麻木了,積極一點是消化了。香港潰敗,存活我城的人,都在摸索自己可以承受的方式,努力生活下去。正如走過強權的捷克、波蘭、南韓、南非、台灣,各自有存活下去的策略。

上Nada的課,著眼於細微的生活小節。同學都是生命自覺的師兄弟,經過多年的修習,習慣觀己於微,自身具體的存在,顏色、味道、聲音、體感,敏於內,觀於外。海德格所說, Being-in-the-world (Dasein),存在的主體與世界相連,這個著名的概念,是哲學的思辯。而 Focusing卻是具體的修習,Being-in-the-world ,觀照身體浮現的意感,安頓於身處社會的氣息。身體存在於具體的情境,與時代緊密相連。 2020 年,香港異變,時代投影到我們的身體、五感、情蘊、價值,在我們的生命留下新的烙印。

我把Focuing、TAE揉合一下,迎接2021年,試試做這樣一種希望的功課。首先要細心覺察自己的變化, Gendlin 提議:choose something you know and cannot yet say, that wants to be said。 在我們漫長的人生裏,有些性格傾向及價值觀,我們都有自知之明;但在某些過渡階段、某些關鍵時刻,內心的悸動,或明或暗,感受往往未能被言說。 Gendlin所指Something cannot yet say就是這種「暗在」的忐忑。2020充滿未被言說的悸動,觸發很多隠而未現的體驗。苦難當前,我們內心有什麼感應?有什麼掀動我們的心思意念? Thinking at the edge,在生活的邊岸,在我們comfort zone的邊沿,在我們習慣了的人生軌跡的三岔口,多一點留意邊沿的微聲,往往對自己、對香港、對世界,會有新的認知。

迎接新的一年,師兄弟之中,有人感到要主動一點維繫朋友之間的友誼,有人想到坦誠一點與家人溝通,有人在思考如何讓自己舒服又優雅地做義務工作,有人在推敲如何運用心理治療的知識幫助親友和學生 ……這些生活上的改變及新嘗試,先用一般坊間的關鍵詞來描述,例如「復原」、「主動維繫友誼」、「義工」、「溝通」 ……Nada請我們從字典去列出這個字眼的「公共意義」( public meaning),去對照自己內心的感受。她說,我們每個人都是獨特的,回應外在的處境,也有獨特的方法。將「公共意義」對照自己內心那確實的 something cannot yet say,字典的解釋往往不能如實描述每個人的經驗:that's not what I meant。我們試試用不同的言詞和字眼,描述內心的意感。

整整一個月,我們各自聚焦在那些個人化的、實在的、卻未能言說的感受。 Nada在後期更邀請我們留意內在矛盾對立的意感,她說 paradox的字根正是promise,矛盾能觸發豐富又多元的新體驗, paradox is a promise!各人的經驗,既有公共性,也有個人的獨到之處。尤其是在社會劇變的轉捩點,慣定俗成的語言,往往不足以承載時代的經驗。用自己的言語,不忌矛盾,把自己回應處境的 something not yet say言說出來,對自己、對社會,是一份嶄新的禮物。

我們討論過的paradox,對各人來說都有自己一番意思﹕「不收分文的義務工作,分文有價」、「停下來,才可以繼續前行」、「經歷懸念,承諾才能圓滿」、「創傷復原,並非回復原貌」、「生命的不確定性,也就是彈性所在」⋯⋯透過內觀,進而以新鮮的語言描述,並在生活上調整舊習慣、實踐新計劃。

我相信港人面對2021年,會不斷作出有血有肉的回應。我相信,在你和我各自的崗位上,也可以作出獨特的貢獻。 Nada是基督徒,她在最後一課引述 Gendlin的話,如果我們回應神聖的呼召,將未能言說的感受,言說並實踐出來,世界就多一份獨特的禮物。這份邀請,若不被言說,它就會隨之而逝。世上沒有另一個你,可以將你的天賦實現出來。面對香港的艱難困局,你和我都可以有新鮮獨到的回應,這也是生命之所在、希望之所在。

Nada最後一課剛好是我的生日,我在日記𥚃寫下我的生日願望:香港詞窮路盡,如何走下去?內心微絲悸動,那是否時代給我們的召喚?停下來,聆聽那沉靜而又堅定的邀請。觀照內心的體驗,原始的、嶄新的,獨特於自我,從未被言說的意感,若能被言說,無論如何渺小,正是一份禮物,天賦得以體現,在當下發揮意義,那是日常生活𥚃,綿綿不絕的希望。