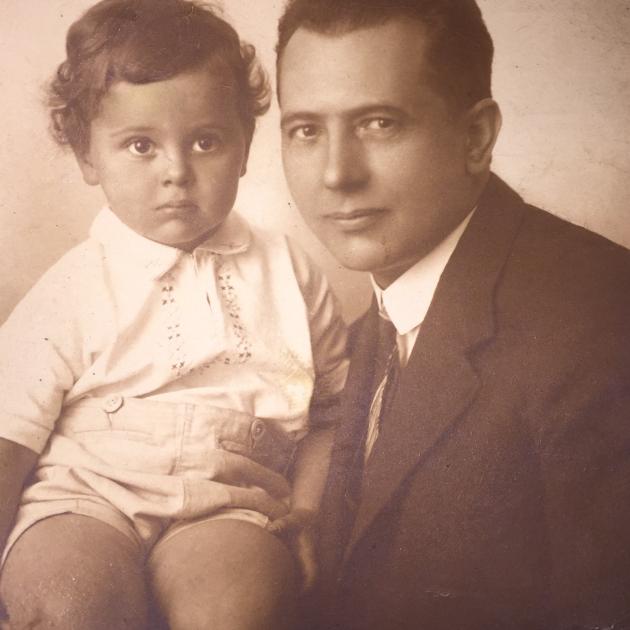

Eugen Gendelin (later Eugene Gendlin) with his father, Leonid, circa 1928 in Vienna, Austria.

This is a transcript of an interview conducted by Ruth Rosenblum and Lynn Preston with Gene Gendlin at his home in Spring Valley, New York in October 2016.

In 2015, I [Ruth Rosenblum] was asked by an Israeli Focusing colleague, “Is Gene Jewish?” I was able to confirm “Yes, he is,” but that was all I could offer. The questions continued “Is his mother Jewish?” since, according to Orthodox Judaism, one’s Jewish status is passed through the mother’s lineage. If the mother is Jewish, the child is Jewish. “Well, yes, I’m almost certain,” I continued, “that Gene and his parents had to leave Vienna when the Nazis came; they were Jewish.”

For years, I’ve been exploring Focusing, meditation and spirituality, and had been interested in the relationship, if any, between Gene’s Jewish identity, heritage and experience, and the development of his philosophy and Focusing. My questions included: Was Gene’s mother, indeed, Jewish? Did his upbringing include participating in religious practices, attending synagogue, engagement in the Viennese Jewish community? and so forth.

Knowing that my teacher and mentor and Gene’s long-time friend and colleague Lynn Preston also had a deep interest in these questions, I asked if perhaps she and I could meet with Gene to discuss these questions. The following is a transcript of two conversations among the three of us (the first held at Gene’s home, the second—at Gene’s request—on the phone) in 2016.

Gene: Well all of it is Jewish, so … the mother was Jewish and her mother was Jewish. What else can I say on that line? I went to Talmud Torah [school where one studies Judaism, the Torah, and learns Hebrew] and my father arranged everything… he wasn't strictly Orthodox, the old way, but his father…the picture was on the wall … [referring to a photograph of his grandfather that was on the wall in his home; such photographs of a grandfather and great-grandfather in traditional dress, wearing a yarmulka and, sometimes, a prayer shawl].

Ruth: I have one of those pictures, too.

Gene: So what else could characterize it quickly?

Ruth: So, your family was observant? Went to synagogue? This is the first time I've heard you’ve been to Talmud Torah. So you had all of it?

Gene: All of it, just not very strict. My father would be in the synagogue all day, but he would read the paper in between. And I understood that very well, so…

Ruth: You were bar mitzvahed?

Gene: I was bar mitzvahed, all the regular things.

Lynn: Were you bar mitzvahed in the States, or in Austria?

Gene: In America, in Brooklyn.

Ruth: Another Brooklynite! Where were you living in Brooklyn? Do you remember?

Gene: Sure. We were living on Read Avenue. I went to P.S. 26—what was P.S. 26 at that time—of course it isn't any more. So what more about Jewish do you want to know?

Ruth: I guess I'm wondering if you have a sense of the role of Jewish, how it has played out in your life. Whether it was in a cultural refugee way or in a religious or theological way.

Gene: It was sort of a mixed-up way, all together, and not in a very orthodox style, but all of them together somehow. I could say…the way my father was… I copied it. I liked it. I agreed with it. It made sense to me. He kept it all but he kept it all his particular way. I never had the Jewish sort of militant way. That way didn't make sense.

Ruth: I once heard Reb Zalman [Reb Zalman Schachter-Shalomi is the founder of the Jewish Renewal movement. Gene and Reb Zalman were Focusing partners for many years. Reb Zalman, until his death in 2014, wanted Focusing to be a part of clergy training.] He was asked if he considered himself a Reform or Conservative or Orthodox. He told the rabbi, who was interviewing him, “I’m orthodox, always, but in a 2011 kind of way. I’m not orthodox from 1800.”

Gene: That’s me, too. So it never bothered me that the theological things were interesting to me. Also in all the other languages. It seemed to me that Jewish was a language or culture. Jewish was us. But then all the other people and all the other theories and all the other…they were also equally somehow, something.

Lynn: You didn't feel a contradiction going to a Catholic college?

Gene: There was no contradiction for me. I went to Catholic University; that was supposed to be the best university in Washington. I don't know what that means but, anyway, I went to a Catholic university. And it was fine. The sisters were teaching, almost everything, and it was okay with me.

Ruth: It's interesting because I had a very, for myself, a strong sense of Catholicism as a child and Reb Zalman was trained in spiritual direction by the nuns.

Lynn: I wonder what being Jewish means in terms of your philosophy. Do you think that that tradition and that culture inform your philosophy?

Gene: Well I think I was just answering it.

Ruth: It’s all kind of connected.

Gene: To me philosophies … you know I have to think a little… philosophy to me …I’m trying to say what it is and that isn't really possible somehow.

Lynn: Well maybe I could ask a little bit smaller. One of my students said, “Please ask Gene if the Implicit is a way of talking about God." She sees the Implicit as circle of the infinite. For her it seems like we're talking about God. She wanted me to ask you about it.

Gene: And the answer would be ABSOLUTELY YES. Sure the Implicit, to me, is how things "mean" or how we are able "to say" in a wider way. So of course it would be God. And then again, just because it's not only in units that are separate doesn't automatically make it God. It's not reversible. The Implicit enables it to be about God but it doesn't necessarily have to be. It doesn’t make any sense, though, if I were to say no.

Lynn: Are you saying it wouldn't be the reverse? God is NOT only the Implicit? You wouldn't reduce God to the Implicit?

Gene: It’s too good a question. I can’t answer the question. I find there are a lot of things that are only recently clear to me that are not possible to be said or done. On the first page of A Process Model I have a lot of that. I say these things on the first page – the event of inhaling as air coming in is the same event as the expanding of the lungs. The inhaling and the coming in is the same event. And that’s how it's alive. But the lungs as a thing, separate from the air as a thing—that’s not the same. The air and the lungs are not the same. But the air coming in is the same as the lungs expanding, so it's the activity that's the same.

Ruth: It's this dance of these two things.

Gene: These two things are not the same as what we normally talk about things. And they’re two different things. I would like to be writing about living things. But that's how living things are. And if I tried to say some definition of living, I mean blah blah blah.... It doesn't work. Why is it going to be whatever you say? It could be anything. It's the instancing of that sameness of the aliveness considered as the "Eveving." [See this paper for more about "Eveving" - "EVerything" interacting with "EVerything" - from Gendlin's philosophy. Note that "Eveving" is capitalized and in quotation marks in the original English on this page so that it is not mis-translated by automated translation services.]

Lynn: The "Eveving," yes.

Ruth: The "Eveving" rather than the thing.

Gene: The "Eveving" is the same.

Lynn: In a way that’s like saying "God is a verb."

Gene: Yeah, right, exactly.

Ruth: I have been very moved by how Focusing and Jewish tradition or Kabbalah intersect so beautifully. In Torah it says, Tell the Israelites "I am that I am,” but as Reb Zalman taught, the translation is not accurate because there are no vowels under the Hebrew letters [vowels denote tense], so what you get is that "I am that I am that I was that I will be" in one moment. And that's what it really means, so that would be a kind of God-ing. It is this constant eveving in the moment where all time is.

Lynn: I think you’re also saying, Ruth, that Focusing and Jewish thinking, theology, seem to be one of a piece.

Ruth: That’s sort of what I was looking at a little bit…things like when you said that thing or the more; in Judaism –you can't make an image of the divine. You know you can't really name God, except one of the names or ways of describing the divine in Kabbalah is Ein Sof, "the boundless one." It felt to me so close.

Gene: That’s right, I agree, if only you don’t make any distinctions, then you have God. And it works.

Ruth: Teilhard de Chardin also talks in those ways, about the divine.

Gene: If you don't make “isms” out of Judaism, then we’re all right. If you do make “isms” it doesn’t work very well. Why should that be so particularly superior as culture or history or group of people? That's not where it is. But it’s right there.

Ruth: I’m understanding that you grew up in a really Jewish environment, in a Jewish community. What did your father do?

Gene: My father was a doctor of chemistry. He went into a dry cleaning business. He got what he called "for boward," which is peasant ties. He lost the sort of high culture level, going to the opera and theater and all that stuff that he had.

Ruth: And did you have that as a child? The opera and so on and so forth, or was that not what your life was like?

Gene: I couldn't say yes or no. I went to school and school is already that.

Ruth: So you went to a public, Jewish or non-Jewish school?

Gene: I went to a public school. The school wasn’t Jewish, I’d say no. It was a good school. It was a city school, until the Nazis came, it was okay. [The Talmud Torah school that is previously referenced is often an after-school program.]

Ruth: What city were you living in?

Gene: Vienna, in the heart of it, in a Jewish neighborhood. It was in the ninth district, which was very Jewish.

Ruth: Did it feel, as a child, comfortable for you? Or were you already aware that being Jewish meant being different from the larger culture?

Gene: That’s a good question. Well, I remember before I went to sleep I would say a prayer. I would say el melech haolam. I still remember that prayer.

Lynn: What does it mean?

Gene: It means God, reality or something. "God the real thing."

Ruth: God the King of the World.

Lynn: The Big Shot.

Gene: And so I knew that that was supposed to be what it is. I don't know how completely… was enough with it to do it.

Ruth: Before the Nazis, did you suffer from anti-Semitism?

Gene: Everybody suffered a little bit but it was more pervasive and less particular.

Ruth: When did you leave Austria?

Gene: 1939, I have to think…and make it correct.

Ruth: That was late!

Gene: We left in September of 1938 perhaps.… I have to think more exactly. They came in 1938. And when they came, my father immediately went to jail. He was arrested immediately. He had enemies. He was culturally very active, so he was part of a cultural top group. That was very fortunate because they gave each other lectures in jail and they had good discussions and interactions. He was very fortunate. His experience wasn't so terrible. And then when they let him out there was a lot of confusion. They didn't know who they would keep locked up and who they would let out. And when he came home it was wonderful. And then we left as soon as we could.

Ruth: So you were with your mother while he was in jail?

Gene: Yeah.

Ruth: Were there other siblings?

Gene: Only child.

Ruth: So here you were a young boy and your father was taken to jail. Wow.

Gene: That was so good, actually. Because my uncle, my father’s younger brother, went to a concentration camp and that was terrible so my father was very lucky. And then we got out. And we got across the border. My father pressured this woman to give him a way across and the way across was that the border guard on Sunday was in church. And there was a replacement. He didn’t know anything about what he was supposed to do and so they knew this ahead of time. So this woman sent us to this little town, a very small town on the border, and next morning we were going to go across. And we did. And it worked.

Ruth: And you went into where?

Gene: To Holland. To the Dutch border. There was a border between Holland and Germany at that point. Then we were four months in Holland and there was a Jewish committee that supported us. Remembering the details makes me cry, but I’m telling about it because I think of it and it doesn't do anything – it’s the telling of it. They gave us twelve gold coins every week and the Dutch authorities agreed not to arrest us, on the committee, but on the streets they would arrest us. So eventually after three months or so my father and I were arrested. Both of us. That was very precarious but by then he already had the documents to go to America so they said we could go. That was very close.

Lynn: Were you terrified to be arrested?

Gene: Well, I don't remember it as an emotional state. I just remember knowing what was what.

Lynn: That it was precarious.

Gene: Yeah. And I remember all the details. I remember that when my father went back upstairs to get the mail before we left in the taxicab, in Vienna, to go out, he brought the affidavit. Again, this is nice to see what moves you. It was this blue envelope. I could see it right here. Because of that we got sent to America instead of having to be sent back some horrible way. So it was a whole lot of very lucky, a lot of luck. So that was that story. What else can I tell?

Lynn: Who was the woman that your father asked to get you across the border?

Gene: I don’t know – I never met her. He told us about her as the good fairy, that’s all.

Lynn: She was Jewish?

Gene: Yes, she was Jewish. It’s peculiar the way that thing worked. There were only so many people left who were Jewish. The very people who helped you get out, some of them didn't go. Which was surprising in a way.

Ruth: They were helping get other people out first.

Gene: He (Gene’s father) brought her to America. She lived in Brooklyn. Everybody lived in Brooklyn.

Lynn: And when you were in Holland, where did you live?

Gene: We lived in a room that was so small that friends said if sunlight came in, you had to go out. And we ate a lot of herring.

Lynn: Tell her about the herring, because we brought some!

Gene: Oh good! The herring was very salty so we left it in water for an hour and then it was very good. I still remember that. It was very good.

Lynn: And they sold it in big barrels on the street?

Gene: Yes, on the street corner.

Ruth: When did you arrive in America?

Gene: January 11th, 1939.

Ruth: Now, today, it’s January 14th 2016. Were there many extended family members left in Austria? Were people killed in camps or did most of the family get out?

Gene: My uncle, he [Gene’s father] brought. And his [Gene's uncle’s] wife. But nobody else got out. I don't remember that they did.

Ruth: And what did your father do when he came here?

Gene: Funny story is that when we woke up in the morning on the first morning that we were here, he was gone. And they worried that he left the wife and child there and disappeared. And what he was doing was typical for him. He was walking Broadway, all the way up from the bottom to the top.

Ruth: He was getting to know this place! He was on the ground here.

Gene: That was funny … and I remember those people very well. They were very good. There were three brothers. One of them, the other two put him through school so he was a dentist. He was a university doctor, dentist. Dr. Parr.

Ruth: It's quite a story.

Gene: It’s always a story.

Ruth: And what was your mother like?

Gene: Well, as long as we had money, we had a cook, right? The yellow sauce with the little green things in it that I hated. And then when it was her [Gene's mother’s] turn she didn't know any cooking at all. All she knew was sort of Italian in a frying pan and turned it around. And the vegetables she just put in the water and boiled and then they were green and they were wonderful. So I loved her cooking. It was all because she didn't know how to cook. So I don’t know if you call that a housewife but it was natural cooking. It was very good. And what else can I tell you?

Ruth: And when she came here, did she ever work outside of the home? What kept her busy?

Gene: No, she didn’t work. She worried about vitamins, which turned out to be right. At that time they didn’t know – my father thought there was only vitamin K. He didn’t believe in vitamins. I think I’m so old because she did all the vitamins.

Ruth: So she had that kind of awareness?

Gene: Yeah.

Lynn: Was she religious? Did she pray?

Gene: Not very religious but not unreligious. Just sort of the way people are when they are not particularly centered on that. They were both very good as far as I was concerned. They didn't treat each other right. But to me they were very good. Both of them. In different ways.

Lynn: Did your father teach you about God, the Bible and the Torah?

Gene: Not that I remember, that’s a good question. I remember that he didn’t talk very much about it. It was like he didn't want to talk about it the way we do about a topic.

Ruth: And in your family, once you were here, did you as a family talk at all much about what had happened or any of that? Because so many families didn’t.

Gene: I don't think we did either but I don’t see why we would have very much. I don’t know … that’s a funny question because I want to say no we didn’t and yet I don't mean we avoided it. It was always there.

Lynn: Were they worrying about you, that you would be safe, after coming from such a dangerous situation?

Gene: That I would be safe? Just me? Oh yeah, they were very… but not related to Jewishness, it seems to me.

Lynn: Just in general?

Gene: I remember when I got very interested in some girl that my father and my mother both followed at a very long distance. It was his basic principle to make sure that the child would be independent, and yet they would make sure that I was okay.

Lynn: Was the girl Jewish?

Gene: Yeah, she was Jewish.

Lynn: Would they be upset if you went out with a girl that wasn't Jewish?

Gene: I don't think I would, but I don't understand where that is. I remember thinking about that. It just seemed natural to me. The other way wouldn’t seem natural to me.

Ruth: You went to high school in Brooklyn?

Gene: No, my father moved us to Washington, DC. That was not very good in many ways. He really didn’t know what he was doing there, in my opinion. He just wanted to get out of Brooklyn. He wanted to get out of the Jewishness. It fit me very well but it didn’t fit him. Washington, DC was segregated.

Lynn: Oh really?

Ruth: Oh, of course.

Gene: It was completely insane.

Ruth: Oh…wow…of course.

Gene: I said in America the Jews are the black people. [Gene meant that the blacks were discriminated against in America, as the Jews were in Austria.] It was a complete shock to me, this whole thing. It was unbelievable.

Ruth: Segregation.

Gene: Yeah. It was unbelievable.

Ruth: Did your father move you into a Jewish community or not at all?

Gene: Well, it was sort of contradictory when I think about it. I definitely remember living for three months in the southeast, with these Jewish people. So he was not avoiding them, but he needed to live in a city that wasn't Brooklyn or something like that. And he moved us first to Hoboken and then to Jersey City then to Washington, DC.

Ruth: Wow, a lot of moves.

Gene: Yeah, a lot of moves.

Lynn: To get away from the Jewishness?

Gene: I thought so. That’s the way I understood it. That he needed to get out of Brooklyn. He couldn't stand Brooklyn. And I could very well.

Lynn: You liked it.

Gene: Brooklyn was very good for me. They put me in in school there you know. They put me…I forgot to tell that story. They put me in the back of the class—all the way back— and the little children …first, second, third fourth grade something like that, were sitting there. Most of them were black with these wonderful hairdos that you could see from the back. Wonderful hairdos, and that way I learned English very very fast. And then my sixth grade teacher told me she found me translating in my mind. I would say “sessel” and then would try to find the word chair. She told me not to do that. Don't translate, just find the English word. And don't translate. And I discovered what I now would consider a source of Focusing. I discovered that it's possible to do that. It’s possible to know that you’re looking at a chair, what that is, without saying it. You don't have to say it. You just know it and then eventually the right word comes. It’s a chair. And so I learned English very fast. And liked it very much, too. I said it sounded like marbles falling down the stairs. It was like, compared to German, it was nice. They were clean sounds. I liked them.

Ruth: And when you were in Washington, what was your father doing? Was he employed?

Gene: He got a good job, I remember, but the years are not clear to me. At some point, he got a good job where he was in charge of that business, and yet it wasn't his. I don't know how many years of that there were but he finally made his own business.

Ruth: So he sort of created his own business.

Gene: Yes he did and I’m sure of that much, but I'm not sure what it was.

Lynn: He had a lot of determination.

Gene: He did?

Lynn: Yeah. Moving all these places and…

Gene: Oh yeah, it was awful at first because the first job he ever got in Brooklyn was in a place, washing with water, these heavy blankets. And he had to lift them. That was very bad. He got a better job. Then he burned his hand, I suddenly remember that now. The doctor told him he couldn’t work. And I remember him saying, “Well, he says that but I have to work anyway.” So frequent that people tell you what they find possible. He didn’t find it possible to not work, so it wasn't very good at first. But then it got better. But then when he moved us to Washington, well, Hoboken was already no good. In Hoboken there were a lot of Germans.

Ruth: There were places that had a German Bund [pro-Nazi organization] already…

Gene: That kind of stuff. But then he moved us to Washington.

Ruth: Seems like that was really difficult for you, for the family, that move.

Gene: I don't know how to say it because you have to go back so many years. That’s … forty.

Ruth: Seventy-five years.

Gene: It's a lot of years. Things were not the same. Very peculiar things, with segregation … very peculiar.

Lynn: And you were really disappointed in America then?

Gene: That it [segregation] existed at all seemed very strange.

Lynn: I know you told me that you loved America when you came. That you felt very at home when you first came here.

Gene: Yeah, that didn't work at all. It really never did. The years are short there somehow. Then I went into the Navy. I was in the Navy.

Ruth: When was that? When did you go into the navy? You joined the Navy?

Gene: Yeah.

Ruth: Do you remember when? Or about how old you were?

Gene: It was about a year into the war. He got me deferred for a year and I went to school that year in Philadelphia. The same principal. He let me go as far as Philadelphia, where he had a brother, so they took care of me. All right… that's enough I think.

Lynn: For the moment.

Gene: Think a minute of anything special you might want still and then we can stop.

Lynn: I wanted to know if the family went to synagogue here. Did you go to synagogue in Brooklyn or in Washington?

Gene: Yeah, I kept the high holidays.

Lynn: But not every week?

Gene: No, not every week, no.

Lynn: And what about now? Do you observe the holidays in any way?

Gene: It took me a long time to get rid of it. I was still doing Yom Kippur, I was trying to…fasting was easy, but not smoking. Not smoking was impossible for me. And I sat there practically paralyzed, sort of depressed and I finally gave that up but it took me a long time to give that up. And again it was this mixture. I didn't grow up having to do that.

Lynn: You wanted to do that. Now, when Yom Kippur comes, do you know it’s that day? Do you think about it?

Gene: Now I pay no attention at all.

Lynn: The rituals aren’t meaningful to you now?

Gene: It’s like I don't have to do them. They’re meaningful all right, if you do them, but not if I do them. I mean Hanukkah and those things are all part of my background.

Lynn: Yes.

Gene: But I didn't do much with them.

Lynn: Do you pray in a formal way…?

Gene: I would say I pray in a way.

Lynn: In a way.

Gene: The way is not so regular now.

Lynn: Like talking to the big system?

Gene: Well it's not so definite around there. So I don’t answer that very good.

Lynn: I think I understand it.

Gene: I believe that everything goes better with God. But then I also see that I'm pushing that on myself. And when I push that on myself then it doesn’t. It doubts it. So I create a whole mess there.

Lynn: It rebels.

Gene: Yeah, I create a mess. And I don’t know how not to at the moment, with this year. (Laughs) You know what I mean?

Ruth: I do.

Gene: And yet I think it’s true.

Lynn: But that seems like the same as in Focusing, where you know things are better with Focusing but you can’t make yourself focus or else you’re rebelling and in a fight with yourself.

Gene: Well I’ve forgotten so much of everything because of this old age problem. And it's just returning. I'm finding that I can remember now how to get a felt sense. It’s …it’s like this way that I was telling you about, what makes something alive is the identity between the coming in and the air. I can go to that, to a felt sense from that, but I can't always go. If I want to say that I’m going to pray, then it doesn’t always do that. It’s something. It’s not very cooperative somehow.

Lynn: But sometimes it does.

Gene: Yeah, sometimes it does.

Ruth: I remember Kevin Krycka, one of the Focusing people from Washington state, saying that Focusing offered him, what he would call "a religious experience," where religions never could offer it to him, that there was something about the quiet and talking—

Gene: Something can actually come.

Ruth: Yes, that you are in this co-creating, that which is listening, which is this dialogue that happens inside in focusing and…

Gene: And he’s without creating a barrier in that same place…

Ruth: Yes, I think, for me, Focusing gave me the opportunity to experience theological concepts that I could see. I could experience that when you are kind or you bring compassion, it's not an abstract. You know, like being good or something. But something different happens.

Gene: Yes.

Ruth: You know, when one can settle down, like in Kabbalah, they talk about concepts, like tzimtzum, pulling back so that something more can be. And so it allows for an experiencing of this bigger thing.

Gene: That’s right.

Ruth: You had once said it can bring you to the door of spirituality. You had said in a conference that Focusing can bring you to a doorway that could lead into that.

Gene: Yeah.

Ruth: One last question: How did you and Reb Zalman get together?

Gene: I don’t remember.

Ruth: But you had a …

Gene: I had some kind of a background with him and I don’t remember it. It’s like that for me… big pieces disappear.

Ruth: Yeah, I get it. Yeah. Is there anything you would like to talk about?

Gene: No, I’m okay.

Ruth: I love hearing the stories. And I so appreciate it. And I'll share it.

Gene: I’m glad we did it.

A few days later, Gene called Lynn and said there was a point he wanted to make, that he’d left out of the previous interview.

ON THE PHONE:

Gene: Hello, hello.

Ruth: Hi Gene. It's Ruth.

Gene: Hello, Ruth. Hello.

Lynn: And it's Lynn. We're all ready for your point.

Gene: Okay, so it's pretty scary to want to talk about God (laughs).

Lynn: Oh okay, I think that's a wonderful way to start, about how scary it is to talk about God.

Ruth: Yeah, yeah.

Lynn: What better thing to talk about, right? What more important thing to talk about?

Gene: It's whatever it is that the whole thing is already and that can't be based on what I do and it can't be waiting to see what I do and it can't be up to what I do. It's what is already happening and I'm in the middle of it, so hello.

Hello. You're right in the middle of it. It's not what you do.

Gene: Surely not dependent on what I do.

Lynn: And yet, what you do is part of it, right? You're part of the system so it also...

Gene: What I wanted to say that I forgot to say when we were talking is I don't think God is Jewish (laughs).

Lynn: I love that.

Ruth: Yeah, yeah.

Gene: God is not Jewish. I'm Jewish. I'm a Jew. I belong to a community and a culture and a history and a tribe and a race and all these things and God is not a member of a tribe or a race or a community. On the other hand, and then this is where it gets difficult, on the other hand, if we didn't have God connected to the community, we wouldn't have holidays and we wouldn't have the Sabbath and we wouldn't have the language and we wouldn't have all this wealth and so surely, it's not wrong to connect God to the community.

Lynn: Absolutely, but do you mean that God isn't Jewish or God is not only Jewish? God is Jewish and Muslim and Christian and every other possible thing as well as Jewish?

Gene: You can certainly say that God is connected to every community and every race and every history and every culture and every language. We can certainly say that and I know I would like to say God is all these other things, each of them, but I would be careful and rather say, "It can't be wrong to connect God to all these things." I think people have trouble with the identity there because the way God is connected to the community, so clearly, comes in a different sense and a secondary sense that's different than God so it's a little bit ... I feel a little bit cautious about saying that God is Jewish and Christian and Muslim and whatever else there, all the other ones.

Lynn: Because of the word "is"? I think, Ruth, you understand that better than I do.

Ruth: I do understand it.

Lynn: What do you understand?

Ruth: From-

Gene: That a philosophical person or a mystic, somebody who understands God that way directly, might be thinking that we're saying that God is this smaller thing and they might also ... You wouldn't blame them to think that they might think that we're saying that God is the abstraction and yet those things are both wrong.

Lynn: God isn't just an idea, an abstraction, but God is not limited to anything, to any...

Gene: Yeah, that's right.

Lynn: ...any smaller thing that's an identity, right?

Gene: Right, so then I want to say it's not wrong and that's pretty cautious or modest. It's not wrong to connect God to anything. It's all right not to know how to say something. If I say it's all right to connect God to anything, then it will work.

Ruth: But it's all right to connect God to anything since it is all connected-

Gene: ...about a feminine version of God or geometric version of God or whatever, that's okay with me, but it doesn't limit what G-O-D can mean and all the other words that that one would maybe substitute. That's what I wanted to say.

Ruth: Thank you for saying that. Do you have any energy that I could ask a question here?

Gene: Sure.

Ruth: First, I'm really very ... I'm moved by what you said and it is scary to talk about this. Do you have some way to talk about, what you have a sense of, what the relationship of how it works, this relationship of each individual to this larger, more-than-that-can-be-known-and-said, thing? When you say that you're a part of it...?

Gene: The big thing that I have here today is it can't possibly be that it all depends on me. That means a lot to me that I'm not yet able to say ... I just found it last night. I found this horror that I'm going to do it wrong or something. Then I realized that in the assumption that it would be a horror, I am assuming that it all depends on me and then I went very nicely to sleep, very nicely, knowing that that solved it. It doesn't all depend on me. I knew that I can't really say all of what's involved and how that solves it but I was grateful that it solves it and I'm still there. I'm still there so it can't all depend on the individual. That's a relationship where you're pointing, isn't it?

Ruth: Yes, it can't all depend on the individual.

Gene: Yeah, so then some way that means more than it seems. Let me see. It seems I'm trying to say, "It's all protected from meaning that it's up to us."

Lynn: The whole big thing is protected from being dependent on any one person or action or...

Gene: Or even any community, either.

Ruth: Right, it's not dependent on us.

Gene: Yeah, and that's as far as I can go. I know I'll get into trouble if I push further than ... so I'm glad right now to have that.

Lynn: Glad it's liberating.

Gene: We can talk next time, any time you want.

Ruth: Thank you.

Gene: I'm glad you did that and thank you for it all.

Ruth: I'm glad I did it too and we did it and I’m incredibly grateful, Gene.

Gene: Thank you, thank you.

Ruth: It's a very important contribution to all of us.

Gene: Thank you for doing it. Blessings.